SPIN (May 2009)

Back in the saddle

No album, no game plan, no problem!

But as No Doubt embark on their first tour in five years, Gwen Stefani and her droogs face the biggest challenge of their career: uncertainty.

“We need this so badly,” says Gwen Stefani in the perpetually questioning accent of a native Cali girl. “We’ve been in a drought for, like, years.” She’s talking about the rain currently pelting the greater Los Angeles area. Presumably.

On an early March afternoon, the platinum blond singer, her hair tied back in a loose ponytail, is looking through the kitchen window of the recording studio where she and bandmates Tony Kanal, Tom Dumont, and Adrian Young have been working on a cover of Adam and the Ants’ “Stand and Deliver.” It’s the first music they’ve recorded together in half a decade.

Stefani wraps her long, thin fingers with shiny French-manicured nails around a mug of PG Tips tea. Her calf-length boots, loose slacks, and turtleneck are all black. “You get desperate trying to write songs,” she says. “Then the opportunity to sing this one came up, and now we’re going on tour – it’s like I got out of doing my homework!”

Five years since their last tour, eight years since their last studio album – the triple-platinum pop-dancehall Rock Steady – and a seeming life time since Stefani became a solo megastar and fashion mogul, she and the boys are re-upping for a 52-date North American safari. If the jaunt goes as well as the band hopes, it should yield a new album. But if the limp economy (though early indicators suggest strong ticket sales) and time apart from fans prove an insurmountable buzzkill? “We can’t think about that shit,” says Kanal. “We have to focus on what we’re doing.”

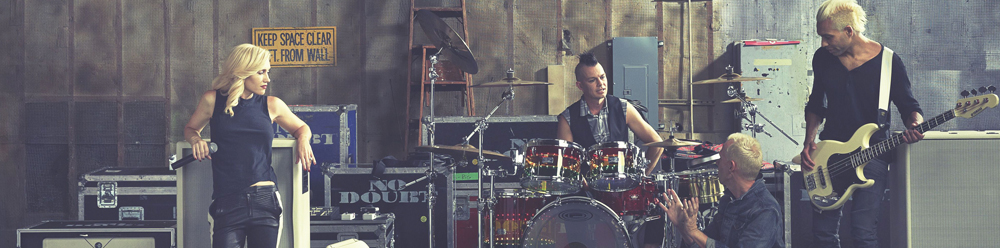

Right now, that means Antmusic. A few hours after Stefani’s rainy-day ruminating, the four old friends and producer Mark “Spike” Stent are assembled in the Hollywood studio, assuming playback position – eyes on the ground, heads bobbing in time to the music. The quartet will mime “Stand and Deliver” for an upcoming appearance on Gossip Girl, whose 18 to 34, predominantly female demo just so happens to be the same consumer group whose pop-culture radar very likely has a Gwen-shaped blip where No Doubt used to be.

For her part, Stefani is no great fan of the show. “[Gossip Girl is] totally the kind of thing I would watch,” she says apologetically, “but if the choice is between sleeping and watching TV, then I’m going to sleep.”

The track is far from finished. Horns to be rearranged. Backing vocals will be tinkered with. The mix will be tweaked. But even in rough shape, No Doubt seem pretty much the same as you remember. At 39, Stefani’s vocal style remains girlishly brash. Dumont, 41 is still a guitarist adept at layering pop sheen and metal crunch. Drummer Young, 39, and bassist Kanal, 38, have retained their gift for shining skank onto even the straightest rock beats, as well as for razzing one another.

“Hey, Adrian, how much did you pay Spike to make your drums so loud?” asks Kanal. looking up from the sofa in the dimly lit studio.

“I didn’t pay him anything,” says Young, his head clean shaven except for a long mohawk that’s slicked straight back and dyed bright red. “I just gave him a pee-pee rub.”

“That reminds me,” says the tall faux-hawked Dumont, “I gotta stop at an ATM later.”

The conversation devolves into Kanal threatening to roofie his drummer before Stefani speaks up. “This is so weird,” she says, beaming. “I can’t believe we’re all here doing this again.”

But what exactly are No Doubt doing? The band never broken up, which means this isn’t quite a reunion. And they don’t have any new music to sell, so the trek – kicking off May 2 in Atlantic City, New Jersey, with a stop the next day headlining the Bamboozle festival – isn’t part of the usual album-tour cycle. Instead No Doubt’s resurfacing is best understood as a kind of referendum on the band’s musical and cultural relevance – a road test, if you will.

“I have no idea what we mean to people anymore,” says Stefani, her legs pulled up beside her on a large L-shaped couch in the studio’s lounge. “I was on tour by myself not that long ago and selling out all over the world. But now,” she shrugs, “do people even go out anymore? The world’s gone crazy.”

The fast-approaching tour has Stefani feeling certain about two things: “We’ll have a blast and get some great ideas for an album.” Well, maybe not certain. “Writing songs is a torturous process. I never know how to do it. The fear is always there that I won’t be able to do it again. So, yeah, if the tour doesn’t sell and we don’t come up with anything, maybe this will be the end of No Doubt. But I highly doubt it.”

To encourage writing, Kanal’s tour bus will be equipped with a mobile recording studio. “We’ve never written on tour before,” says Stefani. “I just need to figure out at what point I’ll be able to get some sleep.”

In person, it takes a moment to adjust to the glamorous luster of Stefani’s candy-apple-red lips and near-geisha complexion. Her famously flat belly is hidden under her shirt. “I’m nowhere near in shape for the tour yet,” she frets, then laughs her short, sharp laugh. “I’m only just now starting to fit into my old clothes!”

Her constantly smiling and wide-eyed son Zuma was born last August. He’s with his nanny down the hall. His older brother, Kingston, 3, is at home with Dad, British rocker Gavin Rossdale. Mom has released two platinum selling albums, 2004’s Love. Angel Music. Baby and 2006’s The Sweet Escape, since No Doubt were last a functioning unit. “Before, when I was with the guys, I didn’t have any kids,” says Stefani, an almond-size diamond sparkling on her wedding ring. “That’s like, whoa – a huge deal. The dynamic of the band is different. It has to be.” She notes, ruefully, that for the first time since they formed 23 years ago, the foursome will be traveling in separate buses.

“When you’ve got the endorphins going from the show, it’s so much fun to be all on the same bus, hanging out and drinking champagne. There’s no way that can happen anymore. I’ve got two babies and their nanny, and an assistant, and my security, and a hairdresser. It’s not much of a party, but that’s what I need in order to perform every night.”

In a sense, the band is back where it started. Formed in Anaheim, California in 1986 – largely an outlet for Gwen’s older brother Eric’s quirky ska-pop – the band’s earliest success was found on the road. A sweaty, energetic live show win them plenty of SoCal fans (and built some strong internal bonds: Kanal and Stefani were in a long-term relationship), but the sound didn’t travel. Their first nine years were spent in limbo between local heroes and national nobodies. “It was so exciting to have a following and know we could go play as far away as San Diego and people would show up,” recalls Dumont from behind the wheel of his black Yukon. He’s dressed in a gray hoodie, black jeans and green Chuck Taylors. The Pacific glistens outside the driver’s side window. “It was hard to understand when our record company called us a failure because we only sold 25,000 copies of our first album.”

They sold some ten million more of their third, 1995’s Tragic Kingdom. (Eric left shortly after the album’s release to pursue a career in animation.) Unabashedly perky and deceptively deep, Kingdom’s deep, “Just a Girl,” “Sunday Morning,” and “Don’t Speak” (about Kanal and Stefani’s breakup) drove a gilded scrunchie deep into grunge’s heart.

But 2000’s Return of Saturn, writer immediately after a marathon two-year tour, traded Kingdom’s primary pop colors for standard post-adolescent revelations in songs such as “Marry Me,” and “Six Feet Under.” The album sold a tenth as many copies as its predecessor. It also planted a seed.

“When we were touring Saturn, the shows weren’t packed to the rafters, but we had a fucking good time,” says Dumont. He’s on the way from his home in Long Beach to pick up a custom-made speaker cabinet in nearby Newport Beach that he plans to use while recording the new album, wherever and whenever that may be.

“That tour was when Tony discovered Jamaican dancehall music. We’d play it backstage for hours after shows – it was all about not worrying and having fun. We ended up going right from that tour into Rock Steady. That was kind of the idea behind what we’re doing now – just getting back into the vibe of being in No Doubt and remembering how awesome that is. Whether we get inspired the same way, we’ll have to see.”

During his time off from the band, Dumont and his wife, Meike, had two sons, Ace, 3, and Rio, 1. He also branched out in to production work, helming two albums by skateboarder turned singer-songwriter Matt Costa.

Taking a hand from the steering wheel to scratch his grey-flecked goatee, Dumont explains how the No Doubt machine creaked back in to action. “I called Tony and Adrian up in 2007 to get together and write. The plan was to have new music ready for Gwen to write lyrics to as soon as she finished touring The Sweet Escape.”

The Gwenless approach worked for the band before, notably on 2002’s “Hey Baby.” It didn’t work this time.

“We hit on a handful of ideas that we might come back to,” says Dumont. “But without Gwen writing lyrics or melodies, there’s only so much we could do.”

It was during a second writing session last winter at a then-pregnant Stefani’s Hollywood home that the band realized what it had to do to feel like a family again. “We needed to have group therapy,” says Stefani, back at the studio. “We would talk about crazy stuff, like how the process that we used before is not gonna work anymore. To be a mom and the lead singer and songwriter and the best friend of these guys,” she pauses, “there was a lot leaning on my shoulders. I couldn’t have a baby, then sit in a studio for a year making an album.”

Kanal also feels the talks were a turning point. “There were some very emotional discussions,” he says. “We’re still under contract for a record, but Interscope appreciates that we have to put out the right record. We have to ease back into this. I understand te skepticism people might have about a band going on tour without any new songs, but this is not us being a nostalgia act. This is not a cash grab. This is a necessary step in No Doubt making another record.”

Dumont remembers that around the same time his band was sorting itself out, he found himself continually clearing up a common misconception. “Everyone thought the band had broken up because Gwen was doing her own thing,” he says. “I’d tell family members that we were working on new music, and they’d go, ‘Really? Who’s singing?’ ”

Adrain Young pulls his metallic green 1962 Park Avenue Cadillac into the parking lot of the Virginia Country Club in Long Beach. He steps out of the car, resplendent in green and blue plaid slacks, a white long-sleeved T-shirt, and a black cardigan – a far cry from the thongs he used to favor onstage. “I’ve been a member for a year,” says the drummer. “My mentor moved here from another golf club. That’s the main reason I joined.”

Young, whose fit build, strong jaw, ramrod posture, and Technicolor clothing make him resemble a psychedelic Marine, plays to a plus-one handicap. His personal best is around 66. For those unfamiliar with golf parlance, that means he’s really fucking good.

“I’m not worried that going on tour will hurt my progress,” says Young, who invested in gonzo golf mag Schwing! in the late ’90s. “I’ll practice in the mornings and play on days off.” He tried to get his son, mason, 7, into the game. “I kind of burned him out already,” he says, frowning. “You can’t force it.”

The plan for this afternoon is to eat and the work with his 9-iron. Young enters the club’s dark wood and oxblood leather dining room and takes a seat at a table near a TV tuned to ESPN. He’s in a feisty mood, and not just because his long game has been giving him problems.

“No Doubt is absolutely still relevant,” says Young. “I don’t know if you know this, but during Gwen’s how in Irvine last June, we did a surprise encore as No Doubt,” he pokes the air with his fork for emphasis, “and that crowd was piercingly loud. Louder than any crowd I remember. That night put to rest any doubt I had about our relevance or legacy.”

Paramore’s Hayley Williams, whose four-men-and-a-lady band is opening for No Doubt this summer, needed no convincing. “I respect them all so much,” she says. “They toured around in a van for years before they blew up. They slept on floors. They’re not a marketing gimmick or a bunch of studio friends. They’re a real band and they’ve had this amazing success. That’s what we all aspire to. All my friends are stoked they’re back.”

The 20-year-old singer has a special love for Stefani. “Gwen is a big deal to me,” Williams says. “She was one of the first people I heard who wrote from a girl’s point of view. I always related to what she was singing about, whether it was ‘Just a Girl’ and being disrespected, or ‘Simple Kind of Life’ and wanting to have a family. I don’t know a girl who doesn’t think of her as a role model.”

Stefani is happy to play the part. “Heaven for me is looking out at the audience and seeing so many young girls,” she says. “On one level, it’s so strange to me that anyone knows who I am, but feeling like I am reaching people and still being respected as a woman is the most rewarding thing.”

But the Stefani that Williams first fell for is not the Stefani of Tragic Kingdom, or even Rock Steady. She married a rock star. Her L.A.M.B fashion label, started in 2003, has been sported on Eva Longoria Parker and Paris Hilton, among others. She set up a companion accessories line, Harajuku Lovers in 2005. Her dance-oriented solo albums, featuring collaborators like Andre 3000, the Neptunes, and Akon, competed and won the world of Xtina and Britney. For a time, she made public appearances accompanied by a quartet of Japanese lovelies dubbed the Harajuku Girls (Think of them as Sanriobric-a-brac – made of people). To some, the fact that Stefani’s decade has been more ooh la la than oi! oi! oi! might seem like a regression.

Stefani doesn’t buy it. “I’m not doing anything now that I haven’t always wanted to do,” she argues, crossing her arms and furrowing her brow. “I’ve always been interested in fashion. I’ve always liked dumb dance music, like Debbie Deb and Club Nouveau. I know it was weird to be on the same circuit with Madonna and Mariah, but I did it my own way. It was campy, it was funny. If people didn’t get it, that’s their problem. People gave me shit about the Harajuku Girls. Seriously? How do you see that that wasn’t meant to be ridiculous?”

She says she’s used to criticism. “When you’re a creative person – and that’s how I define myself – then you’re always going to make somebody mad. Fifteen years ago, when No Doubt started making poppier songs, there were hardcore ska fans who said, ‘Fuck you’.”

So it’s fair to say that No Doubt won’t be playing “Hollaback Girl”? “I’m so over dance music now,” she says. “I had a really specific sound and concept in my head, and I’ve squeezed it out. It’s done. Everyone wants to make it like I ‘left’ the band, but I never planned for my thing to be so big. I always felt like I was cheating on them when I was working with other musicians. In my mind, there was never any question that I was going to come back to No Doubt. Those guys are my best friends forever.”

An older country club member, wearing trousers pulled up to just below his neck, approaches Young, who is finishing up his ahi and brown rice. “That’s some haircut,” he says, motioning to the drummer’s crimson mohawk. The old man’s head is dotted with liver spots.

“Yeah, it is,” says a smiling Young. “You like it?”

“No, I don’t,” the man responds.

Later, Young wallops a long drive into the path of the distinguished gentleman at the opposite end of the driving range. He says it was an accident. Then he does it again.

“If you asked me what I’d like to do every day,” says Tony Kanal at home in the Hollywood Hills, “the answer is playing shows with No Doubt. That’s been my life since I was 16 years old.” On this day, the band’s only childless member is wearing a blue plaid Western-style shirt and skinny black jeans. His black hair is dyed its usual blond. “I’ve always been obsessed with my band. That’s just how I am. But I understand it’s not realistic for everybody else. I’m sure I’d feel different if I had kids.”

Kanal and his live-in girlfriend, Erin, an actress, have been talking about starting a family. He has the band’s blessing. (“I have two boys. Tom has two boys. Adrian has a boy,” says Stefani. “Tony needs to have a girl so the kids can start their own No Doubt.”)

Kanal’s house is a 1925 Spanish Colonial villa that was designed by Stiles O. Clements, the architect responsible for L.A.’s famed Wiltern and Mayan theaters. In a nod to Kanal’s heritage – his parent’s were born in India – a large statue of the Hindu god Ganesha takes pride of place in the foyer. Four cats scamper across the intricately patterned carpets. The modest recording studio on the third floor has an immodest view: On clear days, Catalina Island is visible 20 miles away. Looking northeast, the white dome of the Griffith Observatory rises above the tall palm trees.

The studio is where Kanal, who has the slim build and springy step of a welterweight, retreats to write and record. In the last two years, he produced an album for the reggae singer Elan and did writing an production on Stefani’s solo albums. Along with Dumont and Young, he cowrote “Paralysis,” a track on Scott Weiland’s recent “Happy” in Goloshes. Lately, though, past triumphs are far from his mind.

“It dawned on me that the kids who bought Rock Steady might have outgrown us,” he says. “There are people who didn’t know Gwen was in a band. There are people who will see No Doubt for the first time. It’s a weird thing. You know, going back to when we were playing Fender’s Ballroom in Long Beach in 1987, I had a good sense about who was coming to the shows. Now I don’t really know. It could be anyone.”

The results of a survey posted on No Doubt’s website in late 2008 gave some clues. “The audience is a split you don’t usually see,” explains the band’s manager, Jim Guernot. “Gwen is an influence on very young people and brings them along with her, but there’s also the traditional audience of people in their 30s who have been following the band for 20 years. Concerts usually get one audience or the other, not both. Presales for the tour were tracking at 124 percent higher than they were for Gwen’s tour last year,” he says. “I would’ve been happy if we’d been equal.”

From his lofty perch, Kanal professes allegiance to a power greater than market research. “I’ve had moments of doubt in my life,” he says, “and they’ve been resolved through music. It sounds weird to say, but it’s true.” He continues: “We can push ourselves in a new way. If I didn’t think that we could do that, I would want to call it for what it is. I’d say, ‘Let’s call this a farewell tour’.”

Back in the studio, the final notes of “Stand and Deliver” have long faded away. The band will be back later in the week to listen to a final mix. As Stent gets back to work, Kanal tells Stefani about the radio interviews he was doing earlier that day. “They’re still talking the same shit,” he says to Stefani. Kanal cops the smooth tones of a drive-time DJ, ” ‘I hate to touch a nerve here, Tony, but didn’t you and Gwen used to date?’ ”

Stefani rolls her eyes. “That’s so lame,” she says.

“Try answering questions about thongs,” Young chimes in.

Stefani’s assistant, carrying Zuma, pops in to remind the band that they’re due at the singer’s house to discuss stage designs. Outside, the rain has stopped. The four bandmates get up to leave. Stefani, now holding her son, says anxiously and wistfully, “I want to be out there already.”

Then she speaks again, to everyone and no one, “We still have so far to go.”